History of Products

Saturday, 21 January 2017

Thursday, 5 May 2016

History of Journalism

History of journalism

The history of journalism, or the development of the gathering and transmitting of news, spans the growth of technology and trade, marked by the advent of specialized techniques for gathering and disseminating information on a regular basis that has caused, as one history of journalism surmises, the steady increase of "the scope of news available to us and the speed with which it is transmitted. Before the printing press was invented, word of mouth was the primary source of news. Returning merchants, sailorsand travelers brought news back to the mainland, and this was then picked up by pedlars and travelling players and spread from town to town. This transmission of news was highly unreliable, and died out with the invention of the printing press. Newspapers have always been the primary medium of journalists since 1700, with magazines added in the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century.[1]

Early Journalism[edit]

World[edit]

Before the advent of the newspaper, there were two major kinds of periodical news publications: the handwritten news sheet, and single item news publications. These existed simultaneously.

The Roman Empire published Acta Diurna ("Daily Acts"), or government announcement bulletins, around 59 BC, as ordered by Julius Caesar. They were carved in metal or stone and posted in public places.

In China, early government-produced news sheets, called tipao, were commonly used among court officials during the late Han dynasty (2nd and 3rd centuries AD).

Europe[edit]

In 1556, the government of Venice first published the monthly Notizie scritte ("Written notices") which cost one gazetta,[2] a Venetian coin of the time, the name of which eventually came to mean "newspaper". These avvisi were handwritten newsletters and used to convey political, military, and economic news quickly and efficiently throughoutEurope, more specifically Italy, during the early modern era (1500-1800) — sharing some characteristics of newspapers though usually not considered true newspapers.[3]

However, none of these publications fully met the modern criteria for proper newspapers, as they were typically not intended for the general public and restricted to a certain range of topics.

Early publications played into the development of what would today be recognized as the newspaper, which came about around 1601. Around the 15th and 16th centuries, in England and France, long news accounts called "relations" were published; in Spain they were called "relaciones".

Single event news publications were printed in the broadsheet format, which was often posted. These publications also appeared as pamphlets and small booklets (for longer narratives, often written in a letter format), often containing woodcut illustrations. Literacy rates were low in comparison to today, and these news publications were often read aloud (literacy and oral culture were, in a sense, existing side by side in this scenario).

By 1400, businessmen in Italian and German cities were compiling hand written chronicles of important news events, and circulating them to their business connections. The idea of using a printing press for this material first appeared in Germany around 1600. The first gazettes appeared in German cities, notably the weekly Relation aller Fuernemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien ("Collection of all distinguished and memorable news") in Strasbourg starting in 1605. The Avisa Relation oder Zeitung was published in Wolfenbüttel from 1609, and gazettes soon were established in Frankfurt (1615), Berlin (1617) and Hamburg (1618). By 1650, 30 German cities had active gazettes.[4] A semi-yearly news chronicle, in Latin, the Mercurius Gallobelgicus, was published at Cologne between 1594 and 1635, but it was not the model for other publications.

The news circulated between newsletters through well-established channels in 17th century Europe. Antwerp was the hub of two networks, one linking France, Britain, Germany, and the Netherlands; the other linking Italy Spain and Portugal. Favorite topics included wars, military affairs, diplomacy, and court business and gossip.[5]

After 1600 the national governments in France and England began printing official newsletters.[6] In 1622 the first English-language weekly magazine, "A current of General News" was published and distributed in England[7] in an 8- to 24-page quarto format.

The first newspaper in France, the Gazette de France, was established in 1632 by the king's physician Theophrastus Renaudot (1586-1653), with the patronage of Louis XIII.[8]All newspapers were subject to prepublication censorship, and served as instruments of propaganda for the monarchy. Jean Loret is considered to be one of France's first journalists. He disseminated the weekly news of music, dance and Parisian society from 1650 until 1665 in verse, in what he called a gazette burlesque, assembled in three volumes of La Muse historique (1650, 1660, 1665).

Main articles: History of newspaper publishing § India and List of newspapers in India

The first newspaper in India was circulated in 1780 under the editorship of James Augustus Hickey. Named The Bengal Gazette ,[9] it mainly printed the latest gossip on the British expatriate population in India. On May 30, 1826 Udant Martand (The Rising Sun), the first Hindi-language newspaper published in India, started from Calcutta (nowKolkata), published every Tuesday by Pt. Jugal Kishore Shukla.[10][11] Maulawi Muhammad Baqir in 1836 founded the first Urdu-language newspaper the Delhi Urdu Akhbar. India's press in the 1840s was a motley collection of small-circulation daily or weekly sheets printed on rickety presses. Few extended beyond their small communities and seldom tried to unite the many castes, tribes, and regional subcultures of India. The Anglo-Indian papers promoted purely British interests. Englishman Robert Knight (1825-1890) founded two important English-language newspapers that reached a broad Indian audience, The Times of India and the Statesman. They promoted nationalism in India, as Knight introduced the people to the power of the press and made them familiar with political issues and the political process.[12]

Latin America[edit]

British influence extended globally through its colonies and its informal business relationships with merchants in major cities. They needed up-to-date market and political information. El Mercurio was founded in Valparaiso, Chile, in 1827. The most influential newspaper in Peru, El Comercio, first appeared in 1839. The Jornal do Commercio was established in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1827. Much later Argentina founded its newspapers in Buenos Aires: La Prensa in 1869 and La Nacion in 1870.[13]

Radio and television[edit]

Main article: History of broadcasting

The history of radio broadcasting begins in the 1920s, and reached its apogee in the 1930s and 1940s. Experimental television was being studied before the 2nd world war, became operational in the late 1940s, and became widespread in the 1950s and 1960s, largely but not entirely displacing radio.

Internet journalism[edit]

Further information: Online journalism and online newspapers

The rapidly growing impact of the Internet, especially after 2000, brought "free" news and classified advertising to audiences that no longer cared for paid subscriptions. The Internet undercut the business model of many daily newspapers. Bankruptcy loomed across the U.S. and did hit such major papers as the Rocky Mountain news (Denver), theChicago Tribune and the Los Angeles Times, among many others. Chapman and Nuttall find that proposed solutions, such as multiplatforms, paywalls, PR-dominated news gathering, and shrinking staffs have not resolved the challenge. The result, they argue, is that journalism today is characterized by four themes: personalization, globalization, localization, and pauperization.[14]

Historiography[edit]

Journalism historian David Nord has argued that in the 1960s and 1970s:

- "In journalism history and media history, a new generation of scholars . . . criticised traditional histories of the media for being too insular, too decontextualised, too uncritical, too captive to the needs of professional training, and too enamoured of the biographies of men and media organizations."[15]

In 1974, James W. Carey identified the ‘Problem of Journalism History’. The field was dominated by a Whig interpretation of journalism history.

- "This views journalism history as the slow, steady expansion of freedom and knowledge from the political press to the commercial press, the setbacks into sensationalism and yellow journalism, the forward thrust into muck raking and social responsibility....the entire story is framed by those large impersonal forces buffeting the press: industrialisation, urbanisation and mass democracy.[16]

O'Malley says the criticism went too far, because there was much of value in the deep scholarship of the earlier period.[17]

- Asia[edit]

- Huang, C. "Towards a broadloid press approach: The transformation of China's newspaper industry since the 2000s." Journalism 19 (2015): 1-16. online, With bibliography pages 27-33.

Britain[edit]

- Andrews, Alexander. The history of British journalism: from the foundation of the newspaper press in England, to the repeal of the Stamp act in 1855 (1859). online old classic

- Briggs Asa. The BBC—the First Fifty Years (Oxford University Press, 1984).

- Briggs Asa. The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom (Oxford University Press, 1961).

- Clarke, Bob. From Grub Street to Fleet Street: An Illustrated History of English Newspapers to 1899 (Ashgate, 2004)

- Crisell, Andrew An Introductory History of British Broadcasting. (2nd ed. 2002).

- Herd, Harold. The March of Journalism: The Story of the British Press from 1622 to the Present Day (1952).

- Jones, A. Powers of the Press: Newspapers, Power and the Public in Nineteenth-Century England (1996).

- Lee, A. J. The Origins of the Popular Press in England, 1855–1914 (1976).

- Marr, Andrew. My trade: a short history of British journalism (2004)

- Scannell, Paddy, and Cardiff, David. A Social History of British Broadcasting, Volume One, 1922-1939 (Basil Blackwell, 1991).

- Silberstein-Loeb, Jonathan. The International Distribution of News: The Associated Press, Press Association, and Reuters, 1848–1947 (2014).

- Wiener, Joel H. "The Americanization of the British press, 1830—1914." Media History 2#1-2 (1994): 61-74.

British Empire[edit]

- Cryle, Denis. Disreputable profession: journalists and journalism in colonial Australia (Central Queensland University Press, 1997).

- Harvey, Ross. "Bringing the News to New Zealand: the supply and control of overseas news in the nineteenth century." Media History 8#1 (2002): 21-34.

- Kesterton, Wilfred H. A history of journalism in Canada (1967).

- Pearce, S. Shameless Scribblers: Australian Women’s Journalism 1880–1995 (Central Queensland University Press, 1998).

- Sutherland, Fraser. The monthly epic: A history of Canadian magazines, 1789-1989 (1989).

- Vine, Josie. "If I Must Die, Let Me Die Drinking at an Inn': The Tradition of Alcohol Consumption in Australian Journalism" Australian Journalism Monographs (Griffith Centre for Cultural Research, Griffith University, vol 10, 2010) online; bibliography on journalists, pp 34-39

- Walker, R.B. The Newspaper Press in New South Wales: 1803 – 1920 (1976).

- Walker, R.B. Yesterday’s News: A History of the Newspaper Press in New South Wales from 1920 to 1945 (1980).

United States[edit]

- Barnouw Erik. The Golden Web (Oxford University Press, 1968); The Image Empire: A History of Broadcasting in the United States, Vol. 3: From 1953 (1970) excerpt and text search; The Sponsor (1978); A Tower in Babel (1966), to 1933, excerpt and text search; a history of American broadcasting

- Blanchard, Margaret A., ed. History of the Mass Media in the United States, An Encyclopedia. (1998)

- Craig, Douglas B. Fireside Politics: Radio and Political Culture in the United States, 1920-1940 (2005)

- Emery, Michael, Edwin Emery, and Nancy L. Roberts. The Press and America: An Interpretive History of the Mass Media 9th ed. (1999.), standard textbook; best place to start.

- McCourt; Tom. Conflicting Communication Interests in America: The Case of National Public Radio (Praeger Publishers, 1999) online

- McKerns, Joseph P., ed. Biographical Dictionary of American Journalism. (1989)

- Marzolf, Marion. Up From the Footnote: A History of Women Journalists. (1977)

- Mott, Frank Luther. American Journalism: A History of Newspapers in the United States Through 250 Years, 1690-1940 (1941). major reference source and interpretive history. online edition

- Nord, David Paul. Communities of Journalism: A History of American Newspapers and Their Readers. (2001) excerpt and text search

- Schudson, Michael. Discovering the News: A Social History of American Newspapers. (1978). excerpt and text search

- Sloan, W. David, James G. Stovall, and James D. Startt. The Media in America: A History, 4th ed. (1999)

- Starr, Paul. The Creation of the Media: Political origins of Modern Communications (2004), far ranging history of all forms of media in 19th and 20th century US and Europe; Pulitzer prize excerpt and text search

- Streitmatter, Rodger. Mightier Than the Sword: How the News Media Have Shaped American History (1997)online edition

- Vaughn, Stephen L., ed. Encyclopedia of American Journalism (2007) 636 pages excerpt and text search

Magazines[edit]

- Angeletti, Norberto, and Alberto Oliva. Magazines That Make History: Their Origins, Development, and Influence (2004), covers Time, Der Spiegel, Life, Paris Match, National Geographic, Reader's Digest, ¡Hola!, and People

- Brooker, Peter, and Andrew Thacker, eds. The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines: Volume I: Britain and Ireland 1880-1955 (2009)

- Haveman, Heather A. Magazines and the Making of America: Modernization, Community, and Print Culture, 1741-1860 (Princeton University Press, 2015)

- Mott, Frank Luther. A History of American Magazines (five volumes, 1930-1968), detailed coverage of all major magazines, 1741 to 1930.

- Summer, David E. The Magazine Century: American Magazines Since 1900 (Peter Lang Publishing; 2010) 242 pages. Examines the rapid growth of magazines throughout the 20th century and analyzes the form's current decline.

- Wood, James P. Magazines in the United States (1971)

- Würgler, Andreas. National and Transnational News Distribution 1400–1800, European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History),(2010) Journalists around the world are also arrested.

Source: http://bit.ly/1WMVG4R

Wednesday, 27 April 2016

Monday, 25 April 2016

Wednesday, 13 April 2016

History of Animation.. HMMM.. such a interesting things...

History of animation

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Animation refers to the creation of a sequence of images—drawn, painted, or produced by other artistic methods—that change over time to portray the illusion of motion. Before the invention of film, humans depicted motion in static art as far back as the Paleolithic period. In the 1st century, several devices successfully depicted motion in animated images.

Early approaches to motion in art[edit]

One early example is a 5,200-year old pottery bowl discovered in Shahr-e Sukhteh, Iran. The bowl has five images painted around it that show phases of a goat leaping up to nip at a tree.[1][2]

An Egyptian mural approximately 4000 years old, found in the tomb ofKhnumhotep at the Beni Hassan cemetery, features a very long series of images that apparently depict the sequence of events in a wrestlingmatch.[3] Ancient Chinese records contain several mentions of devices, including one made by the inventor Ding Huan, that were said to "give an impression of movement" to a series of human or animal figures on them,[4] but these accounts are unclear and may only refer to the actual movement of the figures through space.[5]

Seven drawings by Leonardo da Vinci (c. 1510) extending over two folios in the Windsor Collection, Anatomical Studies of the Muscles of the Neck, Shoulder, Chest, and Arm, have detailed renderings of the upper body and less-detailed facial features. The sequence shows multiple angles of the figure as it rotates and the arm extends. Because the drawings show only small changes from one image to the next, together they imply the movement of a single figure.

Although some of these early examples may seem similar to a series of animation drawings, the contemporary lack of any means to show them in motion and their extremely lowframe rate causes them to fall short of being true animation. Nonetheless, the practice of illustrating movement over time by creating a series of images arranged in chronological order provided a foundation for the development of the art.

Animation before film[edit]

Numerous devices that successfully displayed animated images were introduced well before the advent of the motion picture. These devices were used to entertain, amaze, and sometimes even frighten people. The majority of these devices didn't project their images, and accordingly could only be viewed by a single person at any one time. For this reason they were considered toys rather than devices for a large scale entertainment industry like later animation. Many of these devices are still built by and for film students learning the basic principles of animation.

The magic lantern (c. 1650)[edit]

The magic lantern is an early predecessor of the modern day projector. It consisted of a translucent oil painting, a simple lens and a candle or oil lamp. In a darkened room, the image would appear projected onto an adjacent flat surface. It was often used to project demonic, frightening images in a phantasmagoria that convinced people they were witnessing the supernatural. Some slides for the lanterns contained moving parts, which makes the magic lantern the earliest known example of projected animation. The origin of the magic lantern is debated, but in the 15th century the Venetian inventor Giovanni Fontana published an illustration of a device that projected the image of a demon in his Liber Instrumentorum. The earliest known actual magic lanterns are usually credited to Christiaan Huygens or Athanasius Kircher.[6][7]

Thaumatrope (1824)[edit]

A thaumatrope is a simple toy that was popular in the 19th century. It is a small disk with different pictures on each side, such as a bird and a cage, and is attached to two pieces of string. When the strings are twirled quickly between the fingers, the pictures appear to combine into a single image. This demonstrates the persistence of vision, the fact that the perception of an object by the eyes and brain continues for a small fraction of a second after the view is blocked or the object is removed. The invention of the device is often credited to Sir John Herschel, but John Ayrton Paris popularized it in 1824 when he demonstrated it to the Royal College of Physicians.[8]

Phenakistoscope (1831)[edit]

The phenakistoscope was an early animation device.[9] It was invented in 1831, simultaneously by the Belgian Joseph Plateau and the Austrian Simon von Stampfer. It consists of a disk with a series of images, drawn on radii evenly spaced around the center of the disk. Slots are cut out of the disk on the same radii as the drawings, but at a different distance from the center. The device would be placed in front of amirror and spun. As the phenakistoscope spins, a viewer looks through the slots at the reflection of the drawings, are momentarily visible when a slot passes by the viewer's eye.[10] This created the illusion of animation.

Zoetrope (1834)[edit]

The zoetrope concept was suggested in 1834 by William George Horner, and from the 1860s marketed as the zoetrope. It operates on the same principle as the phenakistoscope. It was a cylindrical spinning device with several frames of animation printed on a paper strip placed around the interior circumference. The observer looks through vertical slits around the sides to view the moving images on the opposite side as the cylinder spins. As it spins, the material between the viewing slits moves in the opposite direction of the images on the other side and in doing so serves as a rudimentary shutter. The zoetrope had several advantages over the basic phenakistoscope. It did not require the use of a mirror to view the illusion, and because of its cylindrical shape it could be viewed by several people at once.[11]

In ancient China, people used a device that one 20th century historian categorized as "a variety of zoetrope."[4] It had a series of translucent paper or mica panels and was operated by being hung over a lamp so that vanes at the top would cause it to rotate as heated air rose from the lamp. It has been claimed that this rotation, if it reached the ideal speed, caused the same illusion of animation as the later zoetrope, but because there was no shutter (the slits in a zoetrope) or other provision for intermittence, the effect was in fact simply a series of horizontally drifting figures, with no true animation.[12][13][14]

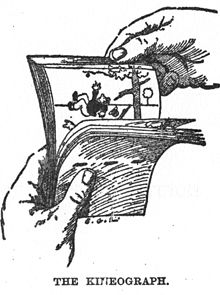

Flip book (1868)[edit]

John Barnes Linnett patented the first flip book in 1868 as the kineograph. A flip book is a small book with relatively springy pages, each having one in a series of animation images located near its unbound edge. The user bends all of the pages back, normally with the thumb, then by a gradual motion of the hand allows them to spring free one at a time. As with the phenakistoscope, zoetrope and praxinoscope, the illusion of motion is created by the apparent sudden replacement of each image by the next in the series, but unlike those other inventions no view-interrupting shutter or assembly of mirrors is required and no viewing device other than the user's hand is absolutely necessary. Early film animators cited flip books as their inspiration more often than the earlier devices, which did not reach as wide an audience.[15]

The older devices by their nature severely limit the number of images that can be included in a sequence without making the device very large or the images impractically small. The book format still imposes a physical limit, but many dozens of images of ample size can easily be accommodated. Inventors stretched even that limit with the mutoscope, patented in 1894 and sometimes still found in amusement arcades. It consists of a large circularly-bound flip book in a housing, with a viewing lens and a crank handle that drives a mechanism that slowly rotates the assembly of images past a catch,size to match the running time of an entire reel of film.

Praxinoscope (1877)[edit]

The first known animated projection on a screen was created in France by Charles-Émile Reynaud, who was a French science teacher. Reynaud created the Praxinoscope in 1877 and the Théâtre Optique in December 1888. On 28 October 1892, he projected the first animation in public, Pauvre Pierrot, at the Musée Grévin in Paris. This film is also notable as the first known instance of film perforations being used. His films were not photographed, but drawn directly onto the transparent strip. In 1900, more than 500,000 people attended these screenings.

Traditional animation[edit]

The first film recorded on standard picture film that included animated sequences was the 1900 Enchanted Drawing, which was followed by the first entirely animated film, the 1906 Humorous Phases of Funny Faces by J. Stuart Blackton—who is, for this reason, considered the father of American animation.

In Europe, the French artist, Émile Cohl, created the first animated film using what came to be known as traditional animationcreation methods—the 1908 Fantasmagorie. The film largely consisted of a stick figure moving about and encountering all manner of morphing objects, such as a wine bottle that transforms into a flower. There were also sections of live action where the animator’s hands would enter the scene. The film was created by drawing each frame on paper and then shooting each frame onto negative film, which gave the picture a blackboard look.

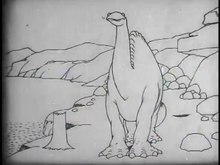

The more detailed hand-drawn animations, requiring a team of animators drawing each frame manually with detailed backgrounds and characters, were those directed by Winsor McCay, a successful newspaper cartoonist, including the 1911Little Nemo, the 1914 Gertie the Dinosaur, and the 1918 The Sinking of the Lusitania.[16][17]

During the 1910s, the production of animated short films, typically referred to as "cartoons", became an industry of its own and cartoon shorts were produced for showing in movie theaters. The most successful producer at the time was John Randolph Bray, who, along with animator Earl Hurd, patented the cel animation process that dominated the animation industry for the rest of the decade.[18]

The silent era[edit]

Charles-Émile Reynaud's Théâtre Optique is the earliest known example of projected animation. It predates even photographic motion picture devices such as Thomas Edison's 1893 invention, the Kinetoscope, and the Lumière brothers' 1894 invention, the cinematograph. Reynaud exhibited three of his animations on October 28, 1892 at Musée Grévin in Paris, France. The only surviving example of these three is Pauvre Pierrot, which was 500 frames long.[19]

After the cinematograph popularized the motion picture, producers began to explore the endless possibilities of animation in greater depth.[20] A short stop-motion animation was produced in 1908 by Albert E. Smith and J. Stuart Blackton called The Humpty Dumpty Circus.[21] Stop motion is a technique in which real objects are moved around in the time between their images being recorded, so that when the images are viewed at a normal frame rate the objects appear to move by some invisible force. It directly descends from various early trick film techniques that created the illusion of impossible actions.

A few other films that featured stop motion technique were released afterward, but the first to receive wide scale appreciation was Blackton's Haunted Mansion, which baffled viewers and inspired much further development.[22] In 1906, Blackton also made the first drawn work of animation on standard film, Humorous Phases of Funny Faces. It features faces that are drawn on a chalkboard and then suddenly move autonomously.

Fantasmagorie, by the French director Émile Cohl (also called Émile Courtet), is also noteworthy. It was screened for the first time on August 17, 1908 at Théâtre du Gymnase in Paris. Cohl later went to Fort Lee, New Jersey near New York City in 1912, where he worked for French studio Éclair and spread its animation technique to the US.

Katsudō Shashin, from an unknown creator, was discovered in 2005 and is speculated to be the oldest work of animation in Japan, with Natsuki Matsumoto,[a][23] an expert in iconography at the Osaka University of Arts[24] and animation historian Nobuyuki Tsugata[b]determining the film was most likely made between 1907 and 1911.[25] The film consists of a series of cartoon images on fifty frames of acelluloid strip and lasts three seconds at sixteen frames per second.[26] It depicts a young boy in a sailor suit who writes the kanjicharacters "活動写真" (katsudō shashin, or "moving picture"), then turns towards the viewer, removes his hat, and offers a salute.[26]Evidence suggests it was mass-produced to be sold to wealthy owners of home projectors.[27] To Matsumoto, the relatively poor quality and low-tech printing technique indicate it was likely from a smaller film company.[28]

Influenced by Émile Cohl, the author of the first puppet-animated film (i.e., The Beautiful Lukanida (1912)), Russian-born (ethnicallyPolish) director Wladyslaw Starewicz, known as Ladislas Starevich, started to create stop motion films using dead insects with wire limbs and later, in France, with complex and really expressive puppets. In 1911, he created The Cameraman's Revenge, a complex tale oftreason,and violence between several different insects. It is a pioneer work of puppet animation, and the oldest animated film of such dramatic complexity, with characters filled with motivation, desire and feelings.

In 1914, American cartoonist Winsor McCay released Gertie the Dinosaur, an early example of character development in drawn animation. The film was made for McCay's vaudeville act and as it played McCay would speak to Gertie who would respond with a series of gestures. There was a scene at the end of the film where McCay walked behind the projection screen and a view of him appears on the screen showing him getting on the cartoon dinosaur's back and riding out of frame. This scene made Gertie the Dinosaur the first film to combine live action footage with hand drawn animation. McCay hand-drew almost every one of the 10,000 drawings he used for the film.[29]

Also in 1914, John Bray opened John Bray Studios, which revolutionized the way animation was created. Earl Hurd, one of Bray's employees patented the cel technique. This involved animating moving objects on transparent celluloid sheets. Animators photographed the sheets over a stationary background image to generate the sequence of images. This, as well as Bray's innovative use of the assembly line method, allowed John Bray Studios to create Colonel Heeza Liar, the first animated series.[30]

In 1915, Max and Dave Fleischer invented rotoscoping, the process of using film as a reference point for animation and their studios went on to later release such animated classics as Ko-Ko the Clown, Betty Boop, Popeye the Sailor Man, and Superman. In 1918 McCay released The Sinking of the Lusitania, a wartime propaganda film. McCay did use some of the newer animation techniques, such as cels over paintings—but because he did all of his animation by himself, the project wasn't actually released until just shortly before the end of the war.[30] At this point the larger scale animation studios were becoming the industrial norm and artists such as McCay faded from the public eye.[29]

The first known animated feature film was El Apóstol, made in 1917 by Quirino Cristiani from Argentina.[31] He also directed two other animated feature films, including 1931's Peludópolis, the first feature length animation to use synchronized sound. None of these, however, survive.[32][33]

In 1920, Otto Messmer of Pat Sullivan Studios created Felix the Cat. Pat Sullivan, the studio head took all of the credit for Felix, a common practice in the early days of studio animation. Felix the Cat was distributed by Paramount Studios, and it attracted a large audience. Felix was the first cartoon to be merchandised. He soon became a household name.

In Germany, during the 1920s the abstract animation was invented by Walter Ruttman, Hans Richter, and Oskar Fischinger, however, theNazis censorship against so-called "degenerate art" prevented the abstract animation from developing after 1933.

The earliest surviving animated feature film is the 1926 silhouette-animated Adventures of Prince Achmed, which used colour-tinted film. It was directed by German Lotte Reiniger and French/Hungarian Berthold Bartosch.

Walt Disney & Warner Bros.[edit]

In 1923, a studio called Laugh-O-Grams went bankrupt and its owner, Walt Disney, opened a new studio in Los Angeles. Disney's first project was the Alice Comedies series, which featured a live action girl interacting with numerous cartoon characters. Disney's first notable breakthrough was 1928's Steamboat Willie, the third of the Mickey Mouseseries. It was the first cartoon that included a fully post-produced soundtrack, featuring voice and sound effects printed on the film itself ("sound-on-film"). The short film showed an anthropomorphic mouse named Mickey neglecting his work on a steamboat to instead make music using the animals aboard the boat.

In 1933, Warner Brothers Cartoons was founded. While Disney's studio was known for its releases being strictly controlled by Walt Disney himself, Warner brothers allowed its animators more freedom, which allowed for their animators to develop more recognizable personal styles.[29]

The first animation to use the full, three-color Technicolor method was Flowers and Trees, made in 1932 by Disney Studios, which won an Academy Award for the work.[19] Color animation soon became the industry standard, and in 1934, Warner Brothers released Honeymoon Hotel of the Merrie Melodies series, their first color films. Meanwhile, Disney had realized that the success of animated films depended upon telling emotionally gripping stories; he developed an innovation called a "story department" where storyboard artists separate from the animators would focus on story development alone, which proved its worth when the Disney studio released in 1933 the first-ever animated short to feature well-developed characters, Three Little Pigs.[34][35][36] In 1935, Tex Avery released his first film with Warner Brothers. Avery's style was notably fast paced, violent, and satirical, with a slapstick sensibility.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs[edit]

Many consider Walt Disney's 1937 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs the first animated feature film, though at least seven films were released earlier. However, Disney's film was the first one completely made using hand-drawn animation. The previous seven films, of which only four survive, were made using cutout, silhouette or stop motion, except for one—also made by Disney seven months prior to Snow White's release—Academy Award Review of Walt Disney Cartoons. This was an anthology film to promote the upcoming release of Snow White. However, many do not consider this a genuine feature film because it is a package film. In addition, at approximately 41 minutes, the film does not seem to fulfill today's expectations for a feature film. However, the official BFI, AMPAS and AFI definitions of a feature film require that it be over 40 minutes long, which, in theory, should make it the first animated feature film using traditional animation.

But as Snow White was also the first one to become successful and well-known within the English-speaking world, people tend to disregard the seven films. Following Snow White's release, Disney began to focus much of its productive force on feature-length films. Though Disney did continue to produce shorts throughout the century, Warner Brothers continued to focus on features.

The television era[edit]

Color television was introduced to the US Market in 1951. In 1958, Hanna-Barbera released Huckleberry Hound, the first half-hour television program to feature only animation.Terrytoons released Tom Terrific the same year.[37] In 1960, Hanna-Barbera released another monumental animated television show, The Flintstones, which was the first animated series on prime time television. Television significantly decreased public attention to the animated shorts being shown in theatres.

Animation Techniques[edit]

Innumerable approaches to creating animation have arisen throughout the years. Here is a brief account of some of the non traditional techniques commonly incorporated.

Stop motion[edit]

This process is used for many productions, for example, the most common types of puppets are clay puppets, as used in The California Raisins , Wallace and Gromit and Shaun the Sheep by Aardman, and figures made of various rubbers, cloths and plastic resins, such as The Nightmare Before Christmas and James and the Giant Peach. Sometimes even objects are used, such as with the films of Jan Švankmajer.

Stop motion animation was also commonly used for special effects work in many live-action films, such as the 1933 version of King Kong and The 7th Voyage of Sinbad.

CGI animation[edit]

Computer-generated imagery (CGI) revolutionized animation. The first fully computer-animated feature film was Pixar's Toy Story (1995).[citation needed] The process of CGI animation is still very tedious and similar in that sense to traditional animation, and it still adheres to many of the same principles.

A principal difference of CGI animation compared to traditional animation is that drawing is replaced by 3D modeling, almost like a virtual version of stop-motion. A form of animation that combines the two and uses 2D computer drawing can be considered computer aided animation.

Most CGI created films are based on animal characters, monsters, machines, or cartoon-like humans. Animation studios are now trying to develop ways to create realistic-looking humans. Films that have attempted this include Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within in 2001, Final Fantasy: Advent Children in 2005, The Polar Express in 2004, Beowulf in 2007 and Resident Evil: Degeneration in 2009. However, due to the complexity of human body functions, emotions and interactions, this method of animation is rarely used. The more realistic a CG character becomes, the more difficult it is to create the nuances and details of a living person, and the greater the likelihood of the character falling into the uncanny valley. The creation of hair and clothing that move convincingly with the animated human character is another area of difficulty. The Incredibles and Up both have humans as protagonists, while films like Avatar combine animation with live action to create humanoid creatures.

Cel-shading is a type of non-photorealistic rendering intended to make computer graphics appear hand-drawn. It is often used to mimic the style of a comic book or cartoon. It is a somewhat recent addition to computer graphics, most commonly turning up in console video games. Though the end result of cel-shading has a very simplistic feel like that ofhand-drawn animation, the process is complex. The name comes from the clear sheets of acetate (originally, celluloid), called cels, that are painted on for use in traditional 2D animation. It may be considered a "2.5D" form of animation. True real-time cel-shading was first introduced in 2000 by Sega's Jet Set Radio for their Dreamcast console. Besides video games, a number of anime have also used this style of animation, such as Freedom Project in 2006.

Machinima is the use of real-time 3D computer graphics rendering engines to create a cinematic production. Most often, video games are used to generate the computer animation. Machinima-based artists, sometimes called machinimists or machinimators, are often fan laborers, by virtue of their re-use of copyrighted materials.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_animation

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)